Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault rose in the House of Commons yesterday for the second reading of Bill C-10, his Internet regulation bill that reforms the Broadcasting Act. Guilbeault told the House that the bill would level the playing field, that it would establish a high revenue threshold before applying to Internet streamers, would not impact consumer choice, or raise consumer costs. He argued that even if you don’t believe in cultural sovereignty, you should still support his bill for the economic benefits it will bring, warning that Canadian producers will miss out on a billion dollars by 2023 if the legislation isn’t enacted. He painted a picture of Internet companies (invariably called “web giants”) that have millions of Canadian subscribers but do not contribute to the Canadian economy,

Guilbeault is wrong. He is wrong in his description of the bill (it does not contain thresholds), wrong about its impact on consumers (it is virtually certain to both decrease choice and increase costs), wrong about the contributions of Internet streamers (who have been described as the biggest contributor to Canadian production), wrong about level playing field claims (incumbent broadcasters enjoy a host of regulatory benefits not enjoyed by streamers), wrong about the economic impact of the bill (it is likely to decrease investment in the short term), and wrong about cultural sovereignty (it surrenders cultural sovereignty rather than protect it).

With the bill starting its Parliamentary review, this is the first in a new series of posts on why a careful examination of the data and the bill itself reveals multiple blunders. There are good arguments for addressing the sector, including tax reform, privacy upgrades, and competition law enforcement. There are also benefits to updating the Broadcasting Act, but in an effort to cater to a handful of vocal lobby groups over the interests of the broader Canadian public, Guilbeault’s bill will cause more harm than good. The series will run each weekday for the next month, first addressing the weak policy foundation that underlies Bill C-10, then a series a posts on the uncertainty the bill creates, a review of the trade threats it invites, and an assessment of its likely impact on consumers and the broader public.

The series begins with a post on the fictional Canadian content “crisis.” Canadians can be forgiven for thinking that the shift to digital and Internet streaming services has created a crisis on creating Canadian content. Canadian cultural lobby groups regularly claim that there is one (Artisti, CDCE) and Guilbeault tells the House of Commons that billions of dollars for the sector is at risk. Yet the reality is that spending on film and television production in Canada is at record highs. This includes both certified Canadian content and so-called foreign location and service production in which the production takes place in Canada (thereby facilitating significant economic benefits) but does not meet the narrow criteria to qualify as “Canadian.” I have written before about the need to revisit the Canadian content qualification rules which enable productions with little connection to Canada to receive certification and some that directly meet the goal of “telling Canadian stories” that fail to do so.

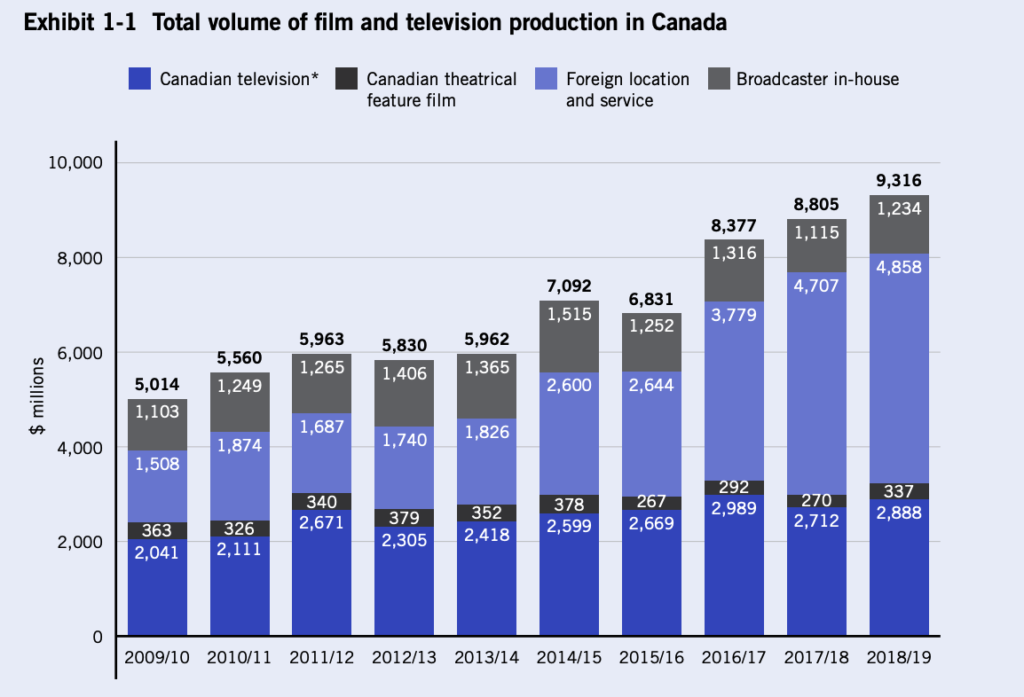

The data on this issue is unequivocal. The overall financing picture shows an industry that has had record amounts of investment in film and television production with the total amount nearly doubling over the past decade. Further, certified Cancon has also grown in recent years, with the top two years for certified Cancon television production occurring over the past three years. In fact, last year was the biggest year for the production of French language Cancon over the past decade.

CMPA Profile 2019, Exhibit 1-1, Pg. 7, https://cmpa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CMPA_2019_E_FINAL.pdf

The data at the provincial level provides further confirmation of record-setting production. Earlier this year, Ontario Creates, the Government of Ontario’s agency for cultural creation, touted a “record breaking year” for Ontario’s film and television production sector, citing more than $2 billion in production spending for 343 productions. Of the $2.1 billion, there was a near-even split between domestic and foreign production: $1.1 billion in foreign production and $1 billion on domestic productions.

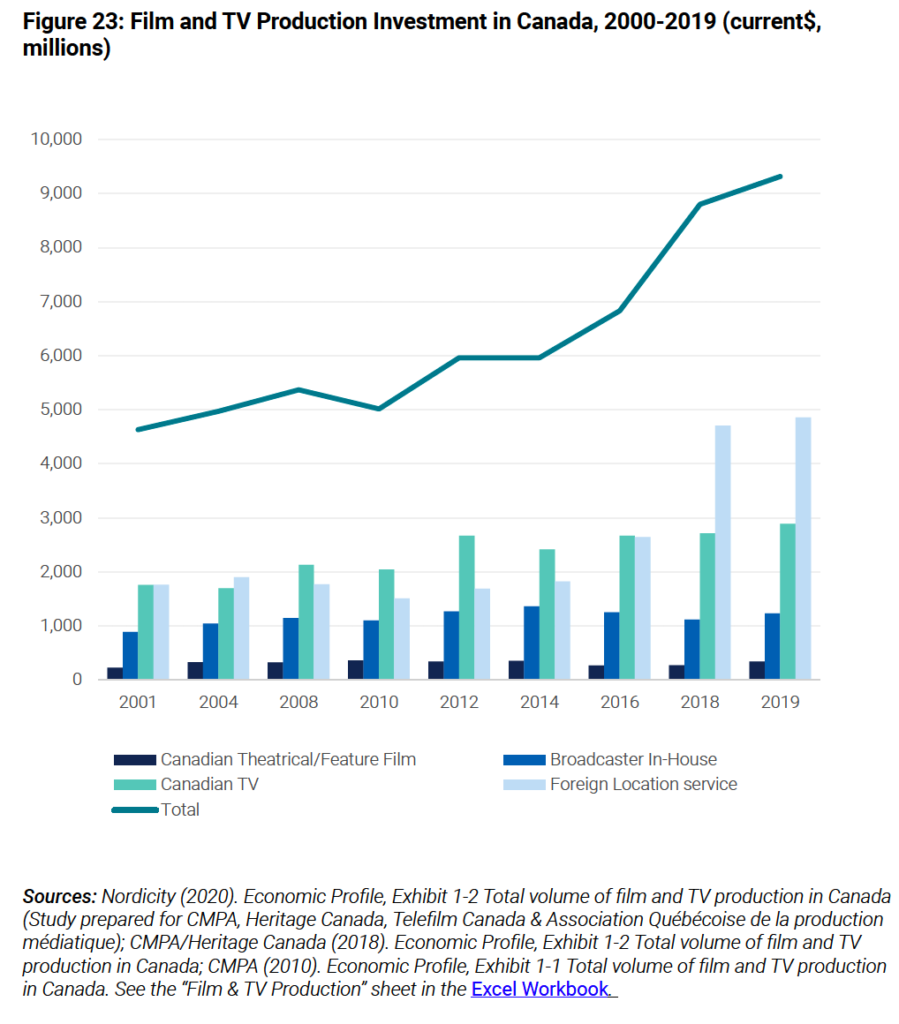

In fact, this week Carleton professor Dwayne Winseck released his annual review of the state of the network economy in Canada. Drawing from multiple sources, he too finds that film and television production investment in Canada has continuously increased for two decades, most recently “driven by massive investments from streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.”

Figure 23, Winseck, Dwayne, 2020, “Growth and Upheaval in the Network Media Economy, 1984-2019”, https://doi.org/10.22215/cmcrp/2020.1, Canadian Media Concentration Research Project, Carleton University.

Notwithstanding the rhetoric, the reality is the politicians and regulators know this to be the case. For example, CRTC chair Ian Scott last year said that Netflix is “probably the biggest single contributor to the [Canadian] production sector today.” Further, at the press conference introducing the bill, Guilbeault acknowledged that the Internet companies are already investing in Canada, but argued that the bill was needed to ensure those investments were not voluntary. Yet production in Canada has grown for years not because of mandatory regulations, but because it is competitive on the world stage. As future posts in this series will demonstrate, Bill C-10 jeopardizes that position.

The post The Broadcasting Act Blunder, Day One: Why There is No Canadian Content Crisis appeared first on Michael Geist.

Comments

Post a Comment