Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing and Education, Part Three: Exploring the Impact of Site Licensing at Canadian Universities

My series on Canadian copyright, fair dealing, and education has thus far explored spending and revenue data at universities and publishers as well as explained why the Access Copyright licence is diminishing in value. This post provides original data on the impact of site licensing at universities across Canada. It is these licences, together with open access and freely available online materials, that have largely replaced the Access Copyright licence, with fair dealing playing a secondary role. Site licensing now comprises the lion share of acquisition budgets at Canadian libraries, who have widely adopted digital-first policies. The specific terms of the licences vary, but most grant rights for use in course management systems or e-reserves, which effectively replaces photocopies with paid digital access. Moreover, many licences are purchased in perpetuity, meaning that the rights to the works have been fully compensated for an unlimited period. The vast majority of these licenses have been purchased since 2012, yet another confirmation that fair dealing has not resulted in less spending on copyright works.

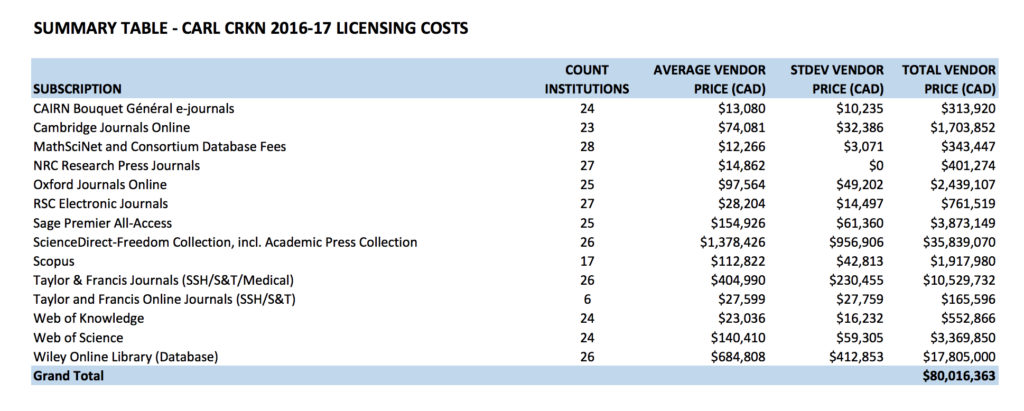

Unlike Access Copyright, which provides minimal detail beyond aggregate numbers on distributions, some universities have provided full open data sets on budgets, acquisitions, and line-by-line costs of subscriptions. For example, recent data released by the Canadian Research Knowledge Network provided details on the subscription expenditures at 28 member libraries from the Canadian Association of Research Libraries. The spending on journals and e-books, even with the benefit of consortium-based negotiations, is enormous. The summary table for 2016-17 licensing costs shows expenditures from those 28 university library alone exceeding $80 million for the year for access to journals, some e-books and other databases.

CARL CRKN Licensing Costs, https://f7f51e08-941e-11e7-aad1-22000a92523b.e.globus.org/1/published/publication_33/submitted_data/SUMMARY_TABLE_CARL_CRKN_2016-17_LICENSING_COSTS.pdf

Other open data sources provide further insights into spending and the breadth of alternative licensing for materials. For example, the University of Alberta’s open data project provides remarkable detail on all subscriptions and purchases by the university library. The data sets show year-by-year, work-by-work pricing, demonstrating that even a single university can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to acquire access to works, many in perpetuity (thanks to University of Alberta’s Trish Chatterley for the assistance).

Those acquisitions extend far beyond journals. For example, last year the university purchased perpetual access to NewspaperARCHIVE Academic Library Edition Canada as part of a $381,617.03 purchase with Proquest that included access a range of materials such as the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times. The Canadian newspaper archive provides perpetual access to over one hundred Canadian newspaper datasets. I am advised that the licence permits copying reasonable portions for educational or research purposes, printing or inter-library loans of materials, and links to articles within electronic reserves or course management systems. The perpetual access includes access to newspapers such as the Winnipeg Free Press, Lethbridge Herald, and Medicine Hat News.

The inclusion of the Winnipeg Free Press is worth highlighting since its publisher, Bob Cox, has been outspoken on the need for copyright reform, yet neglects to mention that he has sold perpetual access to 141 years of the paper’s archives. In other words, licence holders such as the University of Alberta have fully compensated the Winnipeg Free Press for the potential copying of thousands of articles without implicating Access Copyright or fair dealing.

The investment in e-books is the most important trend as it represents a critical alternative to the Access Copyright licence. The committee has already heard from libraries confirming that they have shifted to digital-first purchasing policies, where the digital version of a work is preferred given the greater flexibility the licences typically offer for access and teaching. While some have claimed that the site licensing is largely limited to journals, the reality is that the e-books is a rapidly growing part of university purchasing. At the University of Ottawa, there are now nearly 1.4 million e-books under licence. The University of Alberta dataset shows massive investments in e-books from publishers around the world. For example, last year, it spent over $500,000 for the Springer e-book archive, which provides perpetual access to 110,000 books with the ability to use full chapters for course materials.

With regard to the Canadian component of e-book licensing, the data discussed below suggests that the expenditures and range of Canadian materials is significant (beyond newspapers and Canadian journals). For example, one of the largest Canadian e-book databases comes from the Canadian Electronic Library with a database known as DesLibris. It features thousands of Canadian e-books from Canadian publishers. Last year, the University of Alberta alone spent $24,000 on a licence to access to the database. Assuming that most other universities have done the same, the revenue for a single Canadian e-book database may approach a million dollars annually.

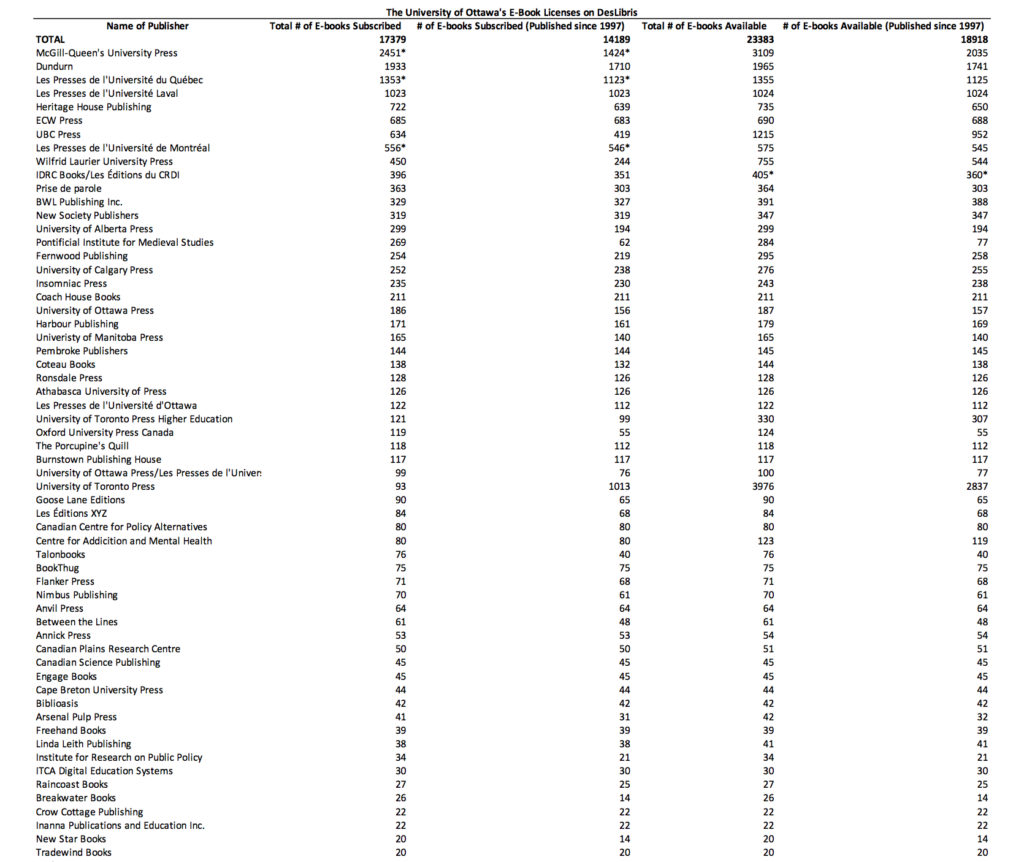

While it is challenging to identify precisely what is covered under the licence at each institution, the University of Ottawa also has a licence to the database. Working with University of Ottawa student Tamara Mascisch-Cohen, we tried to identify the scope of the university’s e-book licences for Canadian publishers within DesLibris (which is just one of several Canadian e-book databases licensed at the university). The University of Ottawa is particularly interesting in this regard since it licences both English and French books from dozens of Canadian publishers (thanks to librarians Tony Horava and Sarah Hill for the assistance).

We looked specifically for four metrics by publisher: number of licensed e-books, number of licensed e-books published since 1997, total number of e-books available, and total number of e-books published since 1997 available. The metrics were designed to provide a sense of licensed e-books from a single database along with a better understanding of how many e-books fell within the last 20 years (Access Copyright says books older than 20 years are rarely copied and are ineligible for its Payback system) and whether the university was purchasing access to the majority of e-books available for subscription. Data on the top 60 Canadian presses is posted below:

University of Ottawa DesLibris data

The data shows a huge investment in Canadian e-books with universities licensing access to thousands of them across dozens of Canadian publishers. In fact, the University of Ottawa approach suggests that universities will typically licence the majority of e-books that are made available by Canadian publishers. In other words, the only thing stopping more e-book licensing are publishers who fail to include them within their databases. Further, there are a sizable number of e-books that are licensed that were published before 1997. These e-books are typically not copied (according to data from Access Copyright) and would not return royalties from the Payback system for the authors or publishers, meaning that site licensing is a crucial way to obtain an ongoing economic return from these older titles.

Moreover, this is only one database. The University of Ottawa library advises that it has purchased perpetual access to more than 15,000 books from Canadian publishers. There are thousands of books from the largest publishers such as University of Toronto Press, McGill-Queen’s University Press, and UBC Press, but dozens of smaller presses have also sold perpetual access.

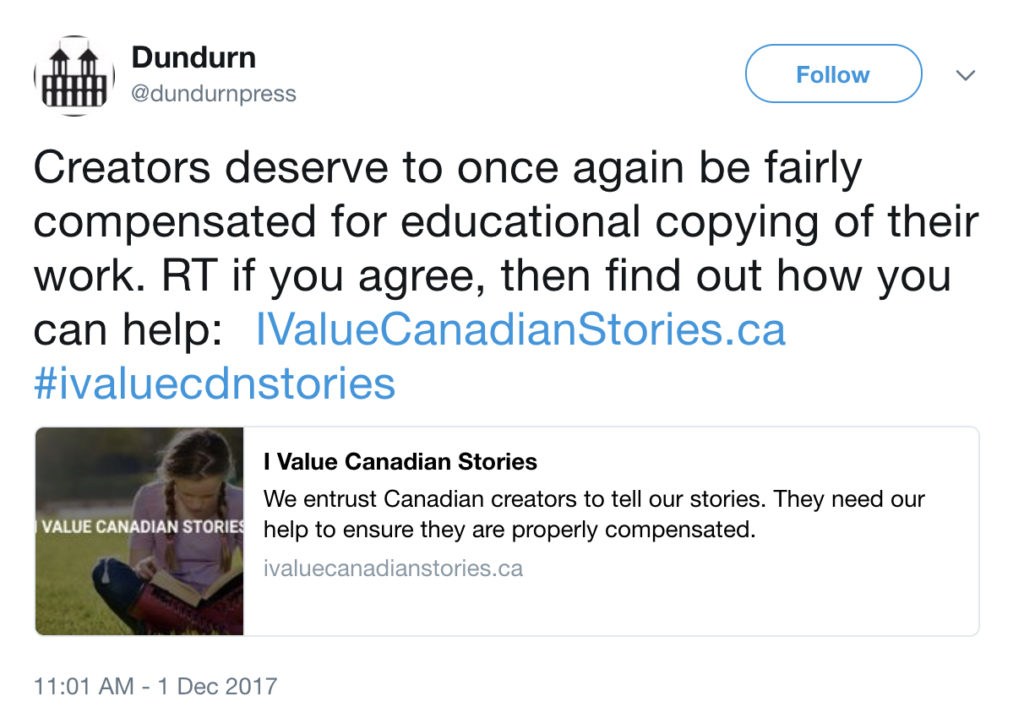

Interestingly, some of the publishers who have been most critical of fair dealing are also the ones that have benefited the most from licensing their e-books to educational institutions. For example, last December, Dundurn Press tweeted:

Dundurn Press tweet, December 1, 2017, https://twitter.com/dundurnpress/status/936626376651755521

What Dundurn Press doesn’t say is that it is compensated for educational use of many of its books. The University of Ottawa has licensed access to over 98% of the Dundurn Press e-books that are available through DesLibris: 1,933 Dundurn Press e-books of a total of 1,965 available e-books through the database. Dundurn has also sold 459 e-books under perpetual licences to the university.

There is similar data for other Canadian publishers. ECW Press, whose site says it has published “close to 1,000 books”, told the industry committee last week that it has lost significant educational adoption revenues. The University of Ottawa has licensed over 99% of the available ECW e-books from DesLibris: 685 out of a total 690. ECW has also sold 339 e-books – about a third of its entire catalogue – under perpetual licences to the university.

Fernwood Publishing, a Canadian publisher that started in Halifax and expanded to Winnipeg, was also discussed during last week’s hearing. It says it has published over 450 titles over the past 20 years. Last week, the committee heard that the educational component of its publishing program has decreased from 70% of sales to about half. The University of Ottawa has licensed 86% of the available Fernwood e-book on DesLibris: 254 out of a total of 295. Fernwood has also sold 186 e-books under perpetual licences to the university. The data is replicated at many Canadian publishers, who criticize fair dealing yet remain silent on the new revenues from site licensing their e-books and on the fact that those licences typically mean that potential copying of their works is paid copying, not copying based on fair dealing.

The story is similar for many Canadian authors, who have had their works licensed under these site licenses. For example, Heather Menzies is an exceptionally accomplished Canadian author who received the Order of Canada in 2013. She is the author of ten books, the former chair of the Writers Union of Canada, and has written publicly about the state of Canadian copyright. Six of her books were published before 1997 and are therefore ineligible for Access Copyright’s Payback system since its data shows titles older than 20 years are unlikely to be copied. Of the remaining four titles, at the University of Ottawa electronic versions of Canada in the Global Village have been licensed through three different databases, No Time is licensed as an e-book, and Reclaiming the Commons has been licensed as an e-book. The library does not have a copy, either paper or electronic, of Enter Mourning.

Ms. Menzies is just one author, but the shift to e-licensing of her works is typically of the trend at universities across the country. Fair dealing is an essential component of copyright law, but it is not the foundation for accessing works in Canadian educational institutions. More relevant is the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on licences that offer greater flexibility and value than the Access Copyright licence. As MPs search for answers, the data makes it clear that fair dealing for education is not problem in need of solving. If anything, there is a need to address ongoing restrictions and barriers in the digital world, a topic that will form the basis for tomorrow’s final post in this series.

The post Canadian Copyright, Fair Dealing and Education, Part Three: Exploring the Impact of Site Licensing at Canadian Universities appeared first on Michael Geist.

Comments

Post a Comment